Comparing yourself to others can lead you to conclude that you are an incompetent fraud. This common element of the so-called imposter syndrome is often seen as an enemy to crush rather than an old friend to walk with.

The thief of joy

When you compare your abilities to those around you, what assumptions are you making? If you’ve ever felt like an imposter at work, I’d be willing to bet that it is, at least in part, because you have endlessly compared yourself to the best in your business. So, what can you do about such behaviour before it stunts your growth?

Consider the following statement:

I often compare my abilities to those around me, and think they might be better than I am.

How much did those words resonate with you?

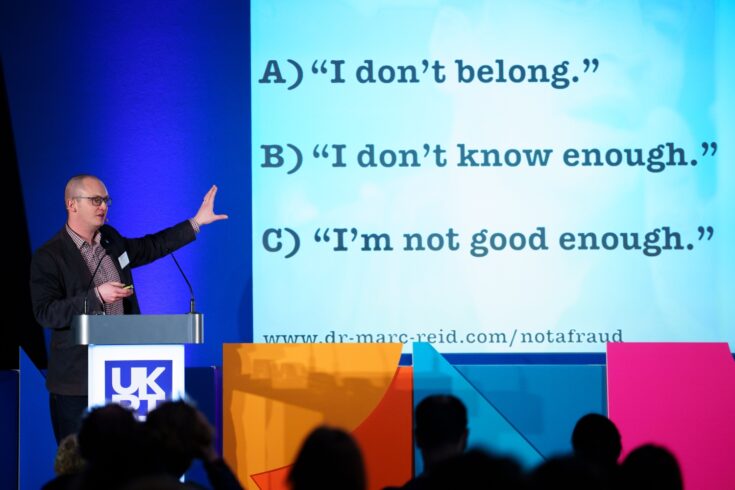

When I surveyed over 100 attendees at the 2024 UKRI Future Leaders Fellows Conference, three out of four people agreed that such comparisons of competence were a regular feature of their daily work. In my own study of the ‘Imposter Phenomenon’, no statement chimed with more emphatic agreement than the one above on comparisons to our peers. Look at my last sentence again. Notice that it reads ‘peers’ and not simply ‘people’. Why?

The comparisons you make between yourself and your peers can be the fuel that lights the fire of your ambition. If taken too far, those same comparisons can reduce your ambitions to ash.

What you have to realise is that this drive for comparison runs much deeper than your own imposter experience. Because the Imposter Phenomenon itself, I would argue, is the birth child of a sociological phenomenon that was first coined during the study of US military in the Second World War.

A wartime origin

When sociology professor Samuel Stouffer studied the morale of soldiers in wartime, he observed a curious difference between Military Police and the Air Corps. Stouffer surveyed men across these two army divisions, and asked the following question:

Do you think a soldier with good ability has a good chance for promotion in the army?

The results, published in a two-volume tome called ‘American Soldier’, unearthed a pervasive concept that now ripples through behavioural science. The Military Police answered the promotion question more positively than did the Air Corps. The Air Corps was better paid, with better conditions, and more frequent promotions than in the Military Police. Why, then, did the apparently worse-off Military Police feel more satisfied than their loftier Air Corps colleagues?

The two different functions rarely encountered one another. We expect that, because the Air Corps had the better set-up, that the Military Police might see their chances of promotion more negatively than their esteemed airborne counterparts. But that’s not what happened at all.

Military Police worked closely with other Military Police who shared the rarity of ever being promoted. Air Corps members compared their position to others in the rapid promotion Air Corps environment. When two related working groups are distant, people in one group compare their situation only to others within the same group, not across groups.

Stouffer realised that comparisons are relative, not absolute. The unexpected result led him to formulate the concept now known as ‘Relative Deprivation’, and it is a key component of what you nowadays call the imposter syndrome.

A personal struggle with comparison

Early in my career, when I learned a young superstar academic was visiting my department, I automatically rushed to compare my career, pound for pound, paper for paper, metric for metric, against this emerging star. I reached the conclusion, neglecting logic or consideration, that I was a fraud. I wondered if I should quit while I was ahead. In this blindingly context-purged panic, I silently dissolved.

Managing social comparison

In many ways, the story of the Imposter Phenomenon is the story of social comparison. You are exposed to myriad systems, metrics and games that would have you – consciously or not – compare yourself to others. The incentives of the game can pressure you to take on the game’s definition of success and forget all about your own.

Feeling like an imposter often arises because you encounter so many situations seeding and cementing the thought that you are a small fish swimming in shark-infested waters.

To manage those imposter thoughts, forget about being the big fish. Be the only fish.

Comparisons are unavoidable. From the wartime curiosities of police and pilots, you now know this behaviour is part of the human condition. Metrics of your workplace can drive these comparisons beyond a means of improving yourself towards a deranged means of concluding that you are always underqualified. Understanding where a metric comes from can help you take it off the pedestal on which you placed it. Whether it’s Michelin Stars (which were invented to sell tyres) or paper citations or grade point averages, appreciating the origin stories of these games can help you focus on the only game of comparison you can ever win… making you now better than you then.