This week saw the launch of a major new funding opportunity by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). An AHRC first, the funding opportunity invites applications to build, host and service a network of national research and development (R&D) facilities for the screen and performance industries.

CoSTAR (Convergent Screen Technologies and performance in Realtime) is an estimated £75.6 million UK Research and Innovation investment over six years (launched in two phases and subject to business case approvals).

It will create national capability to ‘underpin the long-term competitiveness of the UK screen and performance sector.’ It will do so by ‘providing…R&D infrastructure that enables researchers, companies and institutions across the UK to access the facilities, capabilities and insight necessary to ensure that they can conduct world class R&D…to transform the means of production across the screen, performance and allied sectors of the creative industries’.

At its heart, CoSTAR recognises both the risk and opportunity posed to the UK screen and performance industries by the advent and uptake of novel digital technologies. Often referred to by acronym or abbreviation, these virtual production technologies include:

- real-time visual effects (VFX)

- extended reality and haptics

- motion capture (mocap), volumetric capture

- spatial computing

- computer-generated virtual environments

- virtual set scouting and digital fabrication

These technologies are transforming how content is produced, distributed, experienced and consumed. Think of ABBA Voyage with its live orchestra uncannily de-aged, life-size avatars. Or Disney’s ‘The Mandalorian’ which combined physical sets with real-time 3D digital rendering in ways that Director Jon Favreau said “brought the location to the actors”.

In the past, scenes set in Paris or Alaska might have involved transporting cast, crew and kit to these locations. Now, they can be shot in a studio, against a backdrop of giant LED screens showing any location, real or imagined. Once, special VFX were incorporated during post-production. Now, thanks to games engines, actors can work in a virtual environment on set, with VFX pre-planned and run in real time.

The risk here, is that the UK’s traditional strengths – of craft, content and creativity – may be overshadowed. The opportunity, that a carefully-judged public intervention, enabling creative practitioners to experiment with kit that would normally be beyond their means, might unleash new waves of creativity, innovation and growth.

But why…?

You may be asking, why is AHRC the right place to develop this journey from creative production to technological solutions? The answer lies in the inextricable connection between technology and the arts.

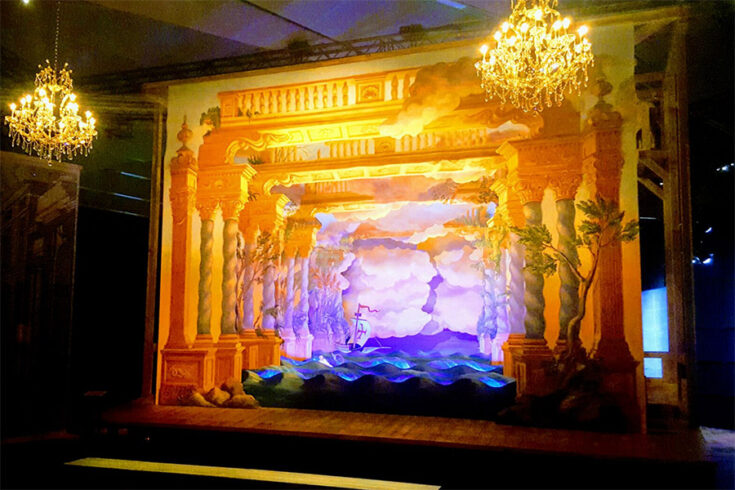

From the ‘dei ex machinis’ of Antiquity, to the fantastical, naval-engineered sets of Baroque opera, history abounds with examples of art and technology coming together to create story, spectacle and beauty.

Moreover, as a more recent example illustrates, when they do come together, it is not as immutable, ready-made wholes that dock seamlessly onto one another, but an iterative, creative process of continuous trial, error, testing and refinement, resulting in an entity that could not otherwise be realised. The best solutions emerge from the midst of collaboration and creative endeavour, in which artists and technologists work as equal partners.

Puppetry and magic

Last July, I had the privilege of visiting the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), along with Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser. We visited their main site in Stratford-Upon-Avon to learn more about how they were beginning to incorporate virtual production into their oeuvre. We met Maggie Bain, the actor who played the part of Cobweb in ‘Dream’ an Audience of the Future (AotF) funded collaboration with the RSC, Marshmallow Laser Feast, Philharmonia and Manchester International Festival.

In many ways, this 50-minute production encapsulates the speed and agility with which the creative sector adapted to retain or capture new audiences in the face of pandemic lockdown. ‘Dream’ was a live, interactive, virtual performance, viewable on devices at home, but connected in real time to the performers. It attracted 80,000 viewers, an entire season of RSC audiences in a mere 10 days.

Maggie gave us an insight into the creative process. The character of Cobweb appears in the show as a giant, disembodied eyeball. Cobweb’s emotions were to be portrayed through a range of movements: blinking, rotation, dilation of the ‘pupil’ etc. Maggie recalled how, at their first meeting with the technical team, they were given a mocap glove. The technologists demonstrated how the giant eyeball could be controlled through the glove by compressing and decompressing thumb and four fingers.

Maggie explained how, as an actor, their job was to ‘embody’ the part. In this instance, they needed to embody the eyeball, inhabit it and transform it into a believable character. No matter that they would be invisible to the audience. Behind the scenes, they needed to think and behave as ‘Cobweb the eyeball’ would do. This was not possible using a hand gesture generally associated with the expression ‘blah, blah, blah.’ Subsequently, the glove was replaced with a full mocap suit and a series of whole-body movements were developed to bring the character to life.

RSC Dream.

Credit: RSC, Marshmallow Laser Feast, the Philharmonia and Manchester International Festival

Why is more investment needed?

So, given the success of ‘Dream’ and other AotF demonstrators, why is more funding needed? Could they not just repeat the process? Put simply, no. Speaking to other AotF demonstrator leads, one word kept recurring: kludge (usually pronounced to rhyme with ‘stooge’). My favourite definition is Wikipedia’s: ‘A kludge or kluge (/klʌdʒ, kluːdʒ/) is a workaround or quick-and-dirty solution that is clumsy, inelegant, inefficient, difficult to extend and hard to maintain.’

In other words, once in production, solutions to issues arising had to be engineered on-the-fly, with little or no time to develop more efficient or standardised workflows. AotF and AHRC’s other major creative economy programme, the Creative Industry Clusters, were like pebbles that created a ripple on the surface of a pond. But the laws of nature dictate that over time, the ripples will cease.

CoSTAR’s purpose is to create the conditions for sustained and sustainable change, with long-term, cumulative benefits. Through CoSTAR, we want to create ripples that are large enough for the pond to break its boundaries, to become a river, a moving, expanding body of skills and knowledge, creativity and expertise, with the capacity to chart new courses, transform landscapes and create new life.

What next?

Over the next few months, AHRC will be organising a series of engagement events (see the sign up event links below) for all those interested in applying to, or being part of a CoSTAR consortium. For more information, please email costar@ahrc.ukri.org

Find out more about this opportunity and apply at: national capability for R&D in screen and performance.

Sign up to the CoSTAR briefing event: Manchester.

Sign up to the CoSTAR briefing event: Midlands.

Sign up to the CoSTAR briefing event: Glasgow.

Sign up to the CoSTAR briefing event: London.

Top image: Theatrical installation inspired by Handel’s Rinaldo (1711) as displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum Opera: Passion, Power and Politics Exhibition, 2017. Credit: the Victoria and Albert Museum