This report collates evidence published during 2025 on the mobility of researchers to the UK. This includes evidence on the attractiveness of the UK to international researchers, drivers of and barriers to mobility, as well as the impact of international mobility and collaboration.

The report distils findings from newly published sources, presented alongside summaries of earlier evidence for context. A fuller overview of the evidence base prior to 2025 can be found in the Global Mobility evidence report 2024 update.

UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) recognises the importance of taking an evidence-led approach to developing policy on international researcher mobility. Since 2022 UKRI has published an annual summary of the evidence base. The 2025 report shares the aim of centralising available evidence on international mobility to stimulate conversations and shape policy developments.

UKRI continue to collaborate with government departments and across the research innovation sector to build the evidence base on international mobility, including to develop this report.

For more details about how this report was created and for definitions of terms used, see the ‘Methodology’ section. Sources for each reference are provided which give further detail on methodologies and any specific limitations. The section on ‘Limitations of the evidence base’ includes some observations on challenges in measuring impact, variation in definitions used in different studies, and limited sample sizes.

We welcome suggestions for additional relevant evidence, recent or forthcoming, to include in this report. To share any suggestions or feedback on this report email globalmobility@ukri.org

2025 context

Introduction

This section summarises recent developments in the research and innovation landscape, highlighting new investments and interventions by the UK government to foster mobility.

During 2025, the UK government made commitments to supporting global talent attraction in the:

- Spending Review

- Immigration White Paper

- UK’s Modern Industrial Strategy

- AI Opportunities Action Plan

Attracting international talent is identified as central to efforts to boost the UK economy and enable growth. These new measures follow on from record levels of investment in research and development in the Autumn 2024 budget.

Elsevier’s Researcher of the Future report suggests that ‘international mobility may be entering a new phase shaped by geopolitics’. Within the current international context, Wellcome advocate that there is the opportunity ‘to create a new role for the UK in the world as the global partner of choice’ for research and development (R&D). This includes through ‘modern, international research partnerships and recognising the benefits of the global exchange of people and ideas’. The Royal Society and American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)’s proposal for ‘Science diplomacy in an era of disruption’ calls for ‘inclusive international scientific collaboration’ and ‘more equitable partnerships in global research collaborations’.

Newly published and forthcoming evidence reviews will explore use of the UK immigration system by sector and profession. The Immigration White Paper sets out the government’s approach to developing a robust evidence base to identify potential sectors with an overreliance on international workers. A Labour Market Evidence Group will inform the creation of workforce strategies to address identified skills shortages.

A review of the IT and engineering professions carried out by the Migration Advisory Committee found that ‘usage of the immigration system is broadly proportionate to the size of the IT and engineering sectors’. The review examines how skills and immigration policy interrelate. It notes that ‘this relationship is complex, and increasing the level of skills in the domestic labour pool does not guarantee reducing migration, as migrant and domestic workers are not perfect substitutes’.

Investment and interventions in the research sector

Looking in more detail at measures introduced by the UK government to support researcher mobility, the Spending Review commits to increasing research and development funding to £22.6 billion per year by 2029 to 2030. This includes to fund association to Horizon Europe, as well as to enable the mobility of global talent to the UK.

Commitments made also include changes to the visa and immigration system, as well as the launch of new global talent initiatives.

Visa and immigration system

The Immigration White Paper outlines how the UK government will ‘go further in ensuring that the very highly skilled have opportunities to come to the UK.’ This includes increasing the number of individuals coming to the UK on ‘very high talent routes’ and making access to these visa routes faster and simpler. These routes include the Global Talent visa (GTV), High Potential Individual visa, and Innovator Founder visa. For example, recent expansion of the eligibility criteria for the GTV fellowships route to include recipients of institutional fellowships.

The Immigration White Paper also commits to an increase in the standard qualifying period for settlement to 10 years. A 12-week consultation was launched in November 2025 setting out detailed proposals. This may identify the impact that proposed changes may have on international researcher mobility.

Expanding eligibility for short-term mobility initiatives, such as the Government Authorised Exchange (GAE) Future Technology Research and Innovation (FTRI) scheme, will support collaboration and skills exchange in research on critical technologies.

The Skilled Worker visa now requires applicants to meet a degree level skills threshold. A Temporary Shortage List (TSL) of roles below degree level was published in July 2025 to allow temporary access to the immigration system. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) was commissioned by the Home Secretary in July 2025 to review the TSL and is approaching this in two stages. In Stage 1, the MAC published a report in October 2025 identifying eligible occupations for inclusion on the TSL. This is because they are potentially crucial to the delivery of the Industrial Strategy or building critical infrastructure. In Stage 2, the MAC launched a call for evidence running from October 2025 to February 2026. Workforce strategies for TSL eligible occupations will be in place for when Stage 2 ends in July 2026.

Changes to the eligibility criteria for the Skilled Worker visa include an increase in the general salary threshold to £41,700 (from £38,700), with continued lower thresholds for science, engineering, technology and mathematics (STEM) PhD holders (Skilled Worker visa: Overview GOV.UK).

Rising visa costs include a 32% increase in the Immigration Skills Charge rate and a 120% increase for Certificates of Sponsorship for the Skilled Worker visa. For small businesses, the Immigration Skills Charge rate will cost £480 per sponsored worker with larger businesses paying £1,320. Employers are prohibited from asking employees to pay the Immigration Skills Charge and now also sponsorship licence costs (Immigration Rules Guidance GOV.UK).

The Immigration White Paper also introduced a reduction in the Graduate visa from 24 months to 18 months for those completing undergraduate and master’s degree programmes. The Autumn 2025 budget sets out that, from the 2028 to 2029 academic year onwards, a levy of £925 per international student per year of study will apply. The levy will not apply to the first 220 international students each year. A government consultation is taking place on the technical detail of the international student levy to inform delivery.

The British Academy’s response to the Immigration White Paper (PDF, 231KB) highlights that international talent is ‘fundamental to the UK’s research and innovation excellence’ and makes recommendations on several policy areas. These include providing further clarity on whether proposed changes regarding indefinite leave to remain apply to Global Talent visa holders, as well as reducing upfront visa costs to ensure the UK’s competitiveness.

The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry has published recommendations to ensure that government aims for the Global Talent visa, as set out in the Immigration White Paper, are achieved. The report highlights opportunities to streamline eligibility criteria and application routes and address misconceptions regarding eligibility. There is also the potential to gather further evidence on how upfront visa and immigration costs (such as the Immigration Health Surcharge) impact on the attractiveness of the UK to international researchers.

Global talent initiatives

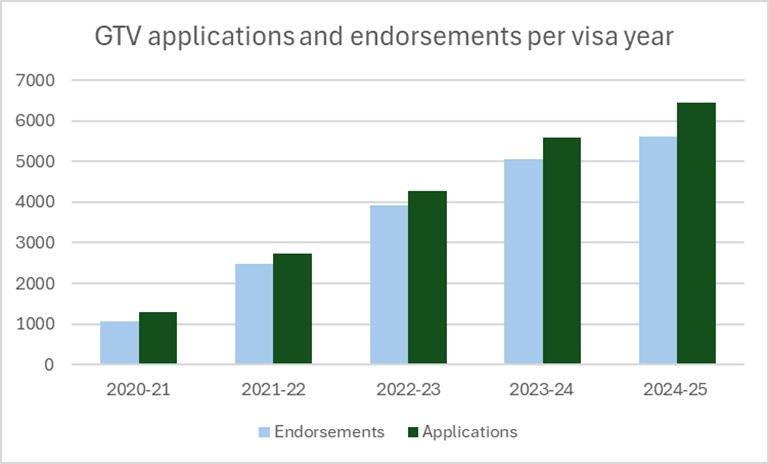

As of December 2025, over 22,000 endorsements have been made by the British Academy, Royal Academy of Engineering, Royal Society, and UKRI for international researchers that have applied for a GTV in the six-year period since the scheme launched.

87% of individuals applying for endorsement have successfully demonstrated their suitability for the science, research and academic GTV routes against the criteria. Individual GTV holders have worked at over 150 different research organisations across the UK to date.

Figure 1: Total GTV applications and endorsements per visa year between 2020 to 2021 and 2024 to 2025, for all science, research and academia endorsing bodies

Total GTV applications and endorsements per visa year between 2020 to 2021 and 2024 to 2025, for all science, research and academia endorsing bodies.

Table 1: Total GTV applications and endorsements per visa year between 2020 to 2021 and 2024 to 2025, for all science, research and academia endorsing bodies

| Visa Year (by unique reference number) | Applications | Endorsements |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 to 2021 | 1290 | 1076 |

| 2021 to 2022 | 2740 | 2491 |

| 2022 to 2023 | 4271 | 3922 |

| 2023 to 2024 | 5598 | 5070 |

| 2024 to 2025 | 6454 | 5618 |

These are indicative figures base on internal monitoring by the GTV Science, Research and Academia endorsing bodies. They have not been quality assured or cleared through official statistics protocol.

New initiatives launched during 2025 to support the attraction and mobility of international researchers to the UK also include the Global Talent Fund and the Global Talent Taskforce.

The Global Talent Fund provides £54 million of funding to 12 UK research organisations to enable them to recruit teams of international researchers. The funding supports research in Industrial Strategy priority areas. Both relocation and research costs are covered, to remove financial barriers to mobility for researchers, team members and their families.

The Global Talent Taskforce was established earlier this year with a clear mission to attract and support exceptional global talent to lay down roots in the UK. This includes exploring ways to reduce barriers and provide greater certainty for internationally mobile individuals looking to spend more time in the UK. It will support researchers, entrepreneurs, investors, top tier managerial and engineering talent and high-calibre creatives to relocate. It will also work closely with the UK’s international presence to network and build a pipeline of talent who want to lay down roots and invest in the UK.

A series of new and expanded fellowships announced during 2025 to support global talent attraction include, for example:

- accelerated international routes for the Faraday Discovery and Green Future Fellowships

- the Turing AI Global Fellowships

- the Encode: AI for Science Fellowship

The government has also announced the Spӓrck AI scholarship programme to fund master’s degrees at nine UK universities specialising in artificial intelligence and STEM subjects.

Within an international context, initiatives have also been announced to support the mobility of researchers to EU countries. These include the €500 million Choose Europe for Science scheme to attract researchers between 2025 and 2027. Through the UK’s association to Horizon Europe, researchers can apply via Pillar 1, Marie Skłodowska Curie Actions and European Research Council grants, to come to the UK.

The Researcher of the Future report also highlights that ‘some countries have implemented policies to keep researchers or encourage them to return, such as attractive funding and the Thousand Talents program in China’.

What makes the UK attractive

Introduction

This section summarises available evidence on the attractiveness of the UK to international researchers.

Drivers and enablers of researcher mobility include:

- opportunities for career progression

- availability of funding

- networking

- pay and benefits

- research infrastructure

The MORE4 study of EU researchers published in 2021 found that career progression was the most commonly cited single reason for international mobility among researchers of all career stages within Europe. The study also found that PhD students appear more opportunity-orientated and focus on the availability of research funding and PhD positions. At post-PhD stage, researchers particularly valued networking, autonomy and opportunities for development.

Funding from research organisations was perceived to be the most important enabling factor for both short-term visits and relocation in a RAND Europe survey of researchers working in higher education around the world.

Evidence base

Existing evidence, published prior to 2025, explores the extent to which the UK is attractive in relation to drivers and enablers including career opportunities, networking, and access to resources and infrastructure.

Career opportunities

The UK generally scores well in terms of career progression in comparison to other European countries. The MORE4 study found that 80.4% of researchers surveyed agreed that career progression is sufficiently merit-based in the UK, and 81.2% of researchers suggested that career paths are transparent.

A 2024 evaluation of the experiences of Global Talent Visa holders (wave 2 report) found that 94% of respondents were motivated to apply for a GTV due to factors related to ‘careers or jobs’. This includes ‘opportunities for career progression (72%)’ and ’role opportunities that matched their specific skills (71%)’.

High-quality peers and the opportunity to build networks and collaborative relationships

The quality of the working conditions influencing scientific productivity are key drivers of the attractiveness of jobs in research, and that drive decisions of researchers to become mobile. These working conditions include working with leading researchers and long-term career perspectives, research autonomy and the balance between teaching and research.

The 2024 evaluation of the experiences of Global Talent Visa holders found that 93% of respondents identified factors relating to ‘professional environment’ as important in deciding to come to or stay in the UK. This includes over half (54%) of respondents mentioning ‘access to professional networks’.

The importance of working conditions and research culture has been identified in a CRUK report on strengthening the UK workforce. The report highlights the need for ‘increasing stability, flexibility and inclusivity’ in research careers to continue to attract and help retain a diverse research workforce.

Funding and pay

The MORE2 study found that researchers were willing to offset some financial benefits, such as pay, in exchange for better quality working conditions that support scientific productivity. These conditions were typically linked to working with leading scientists, long-term career perspectives, research autonomy and the balance between teaching and research.

The 2024 evaluation of the experiences of Global Talent Visa holders found that 29% of respondents identified ‘attractive pay and benefits’ as a factor in deciding to come to or stay in the UK.

The initial 2022 wave of the Research and Innovation Workforce survey found that international workers ‘have been primarily attracted by the career opportunities offered by working in the UK’. This includes working on topics of interest, the opportunity to work with expert colleagues and research facilities, and career progression.

However, almost one-third (30%) of respondents cited ‘pay and benefits, and ‘trying to maintain their standard of living’, followed by ‘visa and immigration requirements’ (24%) as something that made working in the UK difficult. (See sections of the report titled ‘New evidence for 2025’ for findings from the second wave of the survey).

Research infrastructure

Analysis of small-scale case studies of relocating academic staff published in 2013 found that the prestigious reputation of the UK’s research organisations was a significant factor behind choosing the UK to migrate to for work-related reasons.

A factor identified by respondents in the 2024 evaluation of the experiences of Global Talent visa holders was the attractiveness of certain industries within the UK which were described as ‘hubs for innovation.’

New evidence for 2025

Evidence published in 2025 highlights potential fluctuations in motivating factors for researcher mobility from the UK, as well as areas for consideration to ensure the UK remains an attractive destination for international researchers.

Elsevier’s Researcher of the Future report, a global survey of researchers from 113 countries, suggests that ‘researcher mobility is in flux’. The report highlights that ‘fewer researchers are considering relocating abroad now than in 2022’, with a decrease from 34% of all researchers in 2022 to 29% of all researchers in 2025. For researchers in the UK, there was a decrease from 33% to 24%. At the same time, ‘30% of all researchers report seeing more international applicants than a year ago’.

Drivers and enablers of mobility

The second wave of the UK Research and Innovation Workforce survey in 2024 asked those respondents who would potentially consider working abroad in the next five years about their main reasons for this.

In 2024, key reasons included:

- ‘better pay and benefits’ (55% of respondents)

- ‘better work life balance’ (44%)

- ‘access to research funding’ (44%)

- ‘other lifestyle factors’ (41%)

- ‘better research facilities’ (40%)

- ‘opportunities to work on a particular topic of interest’ (36%)

Non-British respondents were more likely than British respondents to select factors including:

- ‘to be near family and friends’ (45% non-British compared to 13% British)

- ‘lower cost of living’ (39% compared to 28%)

- ‘for a family members’ career or education’ (19% compared to 10%)

Comparing responses to the 2022 and 2024 iterations of the survey potentially indicates ‘a decline in the factors motivating individuals to work abroad’.

Both the 2022 and 2024 waves of the survey asked respondents what had influenced their decision to stay in the UK to date.

In 2024, key reasons included:

- ‘personal or family reasons’ (60% of all respondents)

- ‘being from the UK and not having a good enough reason to move’ (39%)

- ‘UK culture and lifestyle’ (30%)

- ‘job security’ (24%)

Comparing responses to the 2022 and 2024 iterations of the survey indicates that respondents to the 2024 survey were significantly more likely to identify reasons to stay as ‘personal or family reasons’ or ‘being from the UK’.

Respondents in 2024 were significantly less likely to report their reason for staying in the UK as being due to certain career-related factors, for example:

- ‘the opportunity to work on a particular topic of interest’ (30% in 2022, to 22% in 2024)

- ‘research facilities’ (29% to 22%)

- ‘educational and training opportunities’ (11% to 7%)

- ‘to work with expert colleagues’ (28% to 23%)

- ‘pay/standard of living’ (17% to 10%)

The study highlights that ‘this shift from professional to personal motivations for staying in the UK may indicate a broader shift in values, where individuals place greater emphasis on personal considerations over career-driven factors’.

Findings of a global survey of researchers in 113 countries presented in the Researcher of the Future report include that top motivations for those considering moving are:

- ‘better work-life balance’ (51%)

- ‘more research funding’ (49%)

- ‘greater freedom to pursue research interests’ (49%)

The study also notes that ‘job security comes through strongly here too, with many researchers saying they would consider moving abroad for’:

- ‘more job opportunities’ (34%)

- ‘a better salary’ (39%)

- ‘a better chance of securing a permanent position’ (22%)

A 2025 Cancer Research UK and YouGov survey of the cancer research workforce found that 96% of cancer researchers involved in international recruitment experienced barriers. The biggest barriers to recruiting international researchers included:

- ‘the impact of Brexit on EU/EAA researcher mobility (78% of respondents)’

- ‘salaries of roles in UK research’ (63%)

- ‘complexity of the UK immigration system’ (58%)

The ‘attractiveness of living in the UK’ was a barrier reported by 42% of respondents. This was noted as being more likely amongst established research leaders, group leaders, and principal investigators (50% of these respondents).

Ensuring UK attractiveness

A study by the University of Southampton looking at mobility of cancer researchers within the EU emphasises that ‘the desire of researchers to collaborate with the UK is as strong as ever’. However, there are factors impacting the attractiveness of the UK to, and the mobility of, EU researchers. These include: ‘changes to immigration policies and visa requirements’, upfront visa costs, uncertainty about career development in the UK, and perceptions that the UK is less welcoming following the UK’s exit from the EU.

A series of case studies collated by the Campaign for Science and Engineering explores barriers in the visa system for 15 UK research and development organisations. Summary findings from the case studies include that ‘the UK is losing its reputation as a welcoming country for researchers’. Current ‘political rhetoric and changing visa policy’ are noted as impacting on both prospective and current international researchers in the UK. This can lead to researchers considering moving to Europe which is seen as ’more accessible and cheaper’.

A report by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry highlights the strengths of the GTV, including an accelerated route to settlement which puts it ‘ahead of nearly all 14 comparator visas’ from other countries. The report also highlights the potential to address misperceptions regarding eligibility criteria and the impact of upfront costs on the route’s competitiveness.

A report on what works to attract individuals into R&D careers includes the potential to ‘attract high skilled international R&D workers by ensuring they are supported to navigate the visa system’. This includes to attract prospective researchers and support retention of existing staff.

See the ‘Barriers to mobility’ section for further evidence on this topic.

Demographics and mobility of the research workforce

Introduction

International mobility can be defined in several different ways, as international experiences can vary by:

- duration

- purpose

- the number and frequency of moves

- when moves occur within a researcher’s career

Studies take different approaches to the researcher groups analysed, as well as whether movements are considered relative to the country of birth or to other reference points. For example, nationality, country of highest degree and education attainment, or country of first research publication.

This section summarises available data on the number of international researchers within the UK workforce. The ‘Areas for future research section’ highlights, further evidence is needed to better understand the demographics of globally mobile researchers in the UK, including the effectiveness of equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) policies.

Evidence base

Evidence published prior to 2025 shows that the UK research population has been rising steadily over the last 10 years.

Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) shows that between 2010 and 2019, the UK saw:

- a 23% increase in the total number of full-time equivalent researchers

- a 35% increase in the total number of full-time equivalent R&D personnel, including technicians and support staff

Data published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 2024 estimated that 17% of all R&D workers are non-UK nationals.

Looking specifically at the international academic workforce in higher education in the UK, data collected by the Higher Education Statistical Agency (HESA) from 2018 to 2023 shows:

- an annual increase in the number of non-EU nationality academic staff

- an annual decrease in the number of EU nationality academic staff

However, these figures do not include all employees involved in research and development activities in higher education institutes, and exclude non-academic staff (for example, technicians) and those in atypical (for example, non-permanent) roles.

New evidence for 2025

New data published by the ONS estimates that 19% of all R&D workers are non-UK nationals.

The data indicates that:

- 81% of R&D workers are of UK nationality

- 10% of R&D workers are of non-EU nationality

- 9% of R&D workers are of EU nationality

During the period from 2009 to 2024, there has been a gradual increase in the proportion of international researchers in the R&D workforce.

Table 2: Nationality of the UK R&D workforce, for the period of 2009 to 2024

| Year | UK nationals | Non-UK nationals | Total R&D workforce |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,520,051 (89%) | 182,509 (11%) | 1,702,560 (100%) |

| 2012 | 1, 483,004 (88%) | 202,216 (12%) | 1,685,220 (100%) |

| 2015 | 1,677,788 (87%) | 248,816 (13%) | 1,926,604 (100%) |

| 2018 | 1,814,322 (85%) | 315,188 (15%) | 2,129,510 (100%) |

| 2021 | 1,931,832 (83%) | 401,139 (17%) | 2,332,971 (100%) |

| 2022 | 2,039,947 (82%) | 447,562 (18%) | 2,487,509 (100%) |

| 2023 | 2,318,003 (83%) | 481,629 (17%) | 2,799,632(100%) |

| 2024 | 2,237,901 (81%) | 513,209 (19%) | 2,751,110 (100%) |

Data sourced from Employment in research and development occupations by nationality, SOC 20 classification, 2021 to 2024. This data draws on both 2010 and 2020 Standard Occupational Codes (SOC). For a defined list of R&D occupations, see: R&D skills supply and demand: long-term trends and workforce projections.

New HESA data published on the international academic workforce in higher education in the UK for the 2023 to 2024 period show that 66% of academic staff had UK nationality, 18% had non-EU nationality and 15% had EU nationality.

Compared to the 2022 to 2023 period, there has been an 11% increase in academic staff with non-EU nationality.

Again, these HESA figures do not include all employees involved in research and development activities in higher education institutes, as they exclude non-academic staff (for example, technicians) and those in atypical (for example, non-permanent) roles.

New data published by the OECD tracks researcher mobility by looking at changes to author affiliations in scientific publications over time. In 2024, the outflow of internationally scientific authors slightly exceeded inflow to the UK, with a negative net flow of minus 0.2 of internationally scientific authors to the UK (as a % of total authors).

Analysis of mobility flows between countries in the 2009 to 2023 period shows that key destinations both for those leaving the UK for, and coming to the UK from, include:

- the US

- Germany

- Australia

The OECD conclude that ‘available indicators suggest that, in most cases, gross flows of talent between countries far exceed net flows, supporting the idea of a “circulation” paradigm’.

Nearly half of respondents (47%) to the UK Research and Innovation Workforce Survey in 2024 reported working outside the UK during their career. One quarter (25%) of all respondents, and one-third (34%) of non-British citizens, reported definite plans to, or potentially strongly considering, working outside the UK in the next five years.

Comparison of the 2022 and 2024 waves of the survey found that those who would ‘strongly consider or already have definite plans to work outside the UK in the next five years statistically significantly decreased’.

The US, Germany and Australia were most frequently identified as potential destinations amongst those respondents to the survey considering future international work. (See sections of the report titled ‘New evidence for 2025’ for further findings from the second wave of the Research and Innovation Workforce Survey).

The Researcher of the Future report identified the ‘top destination countries in 2025’ that researchers across the globe considering relocating would like to move to as:

- Canada (27% of researchers considering relocating)

- Germany (26%)

- US (26%)

The UK appeared in fourth place (25% of researchers considering relocating).

Impact of international mobility and collaboration

Introduction

This section summarises evidence on the impact of international mobility and collaboration for individual researchers, research organisations and countries.

Newly published evidence from the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) shows that 60.4% of UK articles in 2022 resulted from international collaboration, being co-authored with at least one non-UK researcher. There has been a period of sustained growth in international co-authorship between 2018 and 2022, with the UK ranking highest in relation to comparator countries.

One of the most widely known indicators of the impact of research is the field-weighted citation impact (FWCI) of research publications. Evidence indicates a positive correlation between international researcher collaboration and the citation impact of research publications. FWCI is often used as a proxy for measuring the impact of international mobility and collaboration. A key caveat is that FWCI is not only a function of the research but also the publisher and journal. See ‘Limitations of the evidence base’ for a discussion of this metric.

Other proxy measures of impact can include usage (views and downloads) and “alternative metrics” (altmetrics), which measure engagement via a range of online sources.

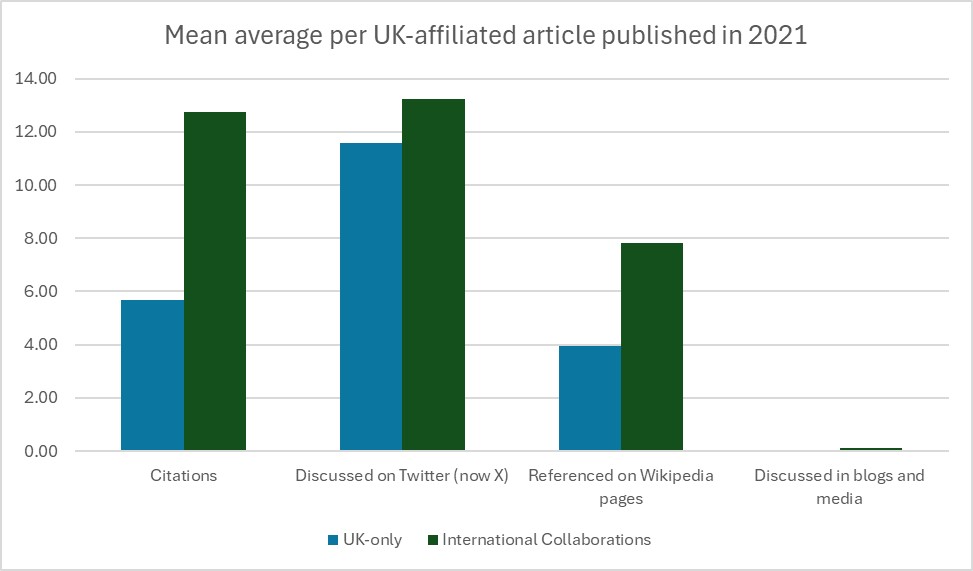

A UKRI-commissioned report by Research Consulting and Sesame Open Science published in 2024 analyses citations (via OpenAlex) and altmetrics (using Crossref Event Data). The underlying dataset associated with this report enables analysis of articles which are outputs from international collaborations (that is collaborations between a UK-based research organisation and an international organisation) and with UK-only outputs (articles which are outputs of a single UK-based organisation or a national UK collaboration). This analysis is for UK-affiliated articles published in 2021 (journal articles with at least one UK-affiliated author,). The report and associated dataset notes for dataset versions provide further information.

When comparing articles resulting from international collaborations to UK-only outputs, we can see that articles resulting from international collaborations are on average more frequently:

- cited

- discussed on X, formerly known as Twitter

- referenced on Wikipedia pages

- discussed in blogs and media

Citations measured here refer to raw citation counts and not the field-weighted citation index. A key caveat of this analysis is the year and field of publication make a significant difference to citation measures. There are likely to be differences in the portfolio of UK-only vs internationally collaborative publications. Certain disciplines can involve more international collaboration than others and garner high citation numbers. This may skew the averages represented in table 3.

It should be noted that the overall averages for discussions in blogs and media are quite small and therefore should not be used to draw meaningful conclusions. Furthermore, all these measures are proxies for impact, so results should be interpreted with some caution and reviewed alongside other measures.

Table 3 – Measuring impact: mean average citations and altmetrics for UK-affiliated articles published in 2021

| Mean average per article | UK only | International collaborations |

|---|---|---|

| Citations | 5.70 | 12.76 |

| Discussed on X, formerly known as Twitter | 11.60 | 13.25 |

| Referenced on Wikipedia pages | 3.95 | 7.84 |

| Discussed in blogs and media | 0.06 | 0.12 |

Figure 2 – Measuring impact: mean average citations and altmetrics for UK-affiliated articles published in 2021

Measuring impact: mean average citations and altmetrics for UK-affiliated articles published in 2021.

Evidence base

Existing evidence suggests that international mobility and collaboration are essential to research and innovation and have impact on researchers, organisations and countries.

Impact of international mobility and collaboration on researchers

Evidence shows that international collaboration is key to career development and enables researchers to:

- build relationships with others in the field and grow networks

- access additional, often specific, expertise, data, infrastructure and resources

- acquire knowledge and develop a range of skills

A survey of more than 1200 researchers by the UK National Academies found that international collaboration and mobility is integral to life as an active researcher across all disciplines and career stages. Short and long-term international mobility are common in the careers of researchers, with short-term trips considered to be becoming more frequent as part of the role of a researcher. The ‘What makes the UK attractive’ section highlights career progression as a key driver of researcher mobility.

The impact of global mobility and collaboration on a researcher can be significant. A survey of researchers working in higher education institutes in the EU in 2019 identified increased or strongly increased effects in the following areas due to mobility experience:

- ‘international contacts or network’ (83%)

- ‘advanced research skills’ (77%)

- ‘recognition in the research community’ (73)

- ‘quality of output’ (72%)

- ‘overall career progression’ (71%)

- ‘quantity of output’ (71%)

- ‘collaboration with other (sub)fields of research’ (70%)

- ‘number of co-authored publications’ (68%)

- ‘job options in academia’ (61%)

- ‘ability to obtain competitive funding for basic research’ (59%)

- ‘national contact or network’ (56%)

- ‘quality of life of you or your family’ (55%)

- ‘understanding or applying Open Science approaches’ (53%)

- ‘progress in salary and financial conditions’ (50%)

- ‘job options outside academia’ (46%)

Source: MORE4 Publications Office of the EU.

A systematic review of studies on how international mobility impacts on scientists’ careers found that most published studies explore longer-term periods abroad and focus on those employed in Europe at academic institutions.

Many studies conclude that international mobility is beneficial to scientists’ careers, as mobility can foster collaboration, increase publications and patents, and may enable access to positions with better pay or of greater status.

Mobility experiences can enable scientists to acquire or transfer knowledge and skills, and to access research funds and infrastructure.

However, mobility may lead to career instability, including risks in being disconnected from research networks in one’s home country, and entail limits in transferring social security entitlements.

Potential ‘trade-offs on a personal level’ are also noted in a Royal Society-commissioned literature review on international mobility, including ‘loss of social ties’ and ‘challenges associated with mobility for those with a partner and children’.

Impact of international mobility and collaboration on organisations

Existing evidence identifies a range of benefits for organisations resulting from international collaboration.

A 2024 UKRI-commissioned literature review identified both ‘direct benefits’ to R&I for organisations involved in international collaboration (such as ‘better bibliometric research outputs’ and ‘talent development’). It also showed broader benefits including ‘knowledge spillovers, societal and reputational benefits, national competitiveness and economic growth’.

The review found it was widely understood that ‘organisations that collaborate internationally tend to perform better because they can access resources (knowledge, talent, data and infrastructure) that are not available to their domestically focused counterparts’. This may include access to researchers with specialist skills and diverse knowledge.

The review also considered the impact of international collaboration relative to domestic collaboration or no collaboration, and the impact resulting from international collaboration between different types of organisations. Findings included that ‘international collaborations between universities and businesses (U2B) and between businesses (B2B) can lead to better outcomes than domestic partnerships, such as:

- higher levels of patenting activity

- business growth

- profitability

- innovation performance

Impact of international mobility and collaboration on countries

Existing evidence highlights how global mobility creates benefits for both host countries and countries of origins, enabling ‘brain circulation’, as the movement of researchers back and forth helps knowledge to circulate worldwide. There are both financial and non-financial benefits.

The UKRI-commissioned literature review found that the researchers and organisations most likely to benefit from international collaboration were ‘those with higher research capabilities, absorptive capacity, and innovation novelty’. However, when considering benefits at national level found ‘emerging countries potentially having more to gain from collaborating internationally.’ Furthermore, ‘the more firms within a country engage in international R&D collaboration, the more competitive the country becomes’.

Evidence published by the British Academy (PDF, 612KB) indicates that enabling UK-based researchers to undertake short periods of time overseas is beneficial to the UK’s soft power. This also helps to establish and reinforce bilateral and multilateral research and innovation relationships between countries but also beyond.

A report published by Universities UK International shows both the economic benefits of international students to the UK economy and the non-financial contributions of international postgraduate research students. This includes by bringing skills and via collaborations which contribute directly to the UK’s research base and publications, as well as in making PhD programmes successful and projecting the UK’s soft power.

New evidence for 2025

New reports published during 2025 provide further insights on the impact of international mobility and collaboration for researchers and countries, including the UK.

Impact of international mobility and collaboration on researchers

New analysis by RAND has sought to identify ‘pre-move predictors of individual researcher success after an international move’. The study utilised publication data to identify internationally mobile authors and to explore specific outcomes including publication volume, citation impact, and author affiliations. Findings include that ‘researchers who have a strong track record, routinely operate within large teams, are mature in their career, and have prior international collaboration experience are more likely to thrive after relocating’.

A new report by Universities UK International on student mobility trends includes analysis of HESA data on students graduating from UK universities between 2017 to 2018 and 2021 to 2022. The data suggests that mobility experiences are correlated with ‘better outcomes in terms of first-class degree awards, rates of unemployment, professional-level employment and higher graduate salaries’. However, this analysis ‘cannot account for the self-selecting nature of mobility and other contextual factors’. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic and new visa requirements for European mobility following the UK’s exit from the EU. The report makes several recommendations for government and the sector. This includes the continuation of widening participation initiatives to foster future mobility.

Impact of international mobility and collaboration on countries

Evidence published by the Russell Group highlights how international collaboration contributes to economic growth and supports the UK’s soft power. For example, analysis of patent data carried out by Jisc for the Russell Group shows that ‘since 2018, UK universities have filed over 100 EU, US and UK patents a year with one or more international partners every year, only partly overlapping with licensing activity’.

International collaboration also ‘supports our Industrial Strategy by boosting the research disciplines which underpin it’ (as evidenced via international co-authorship of publications in a range of disciplines, using data provided by the British Council). It also enables progress in critical technology areas and brings international investment in research and development. Furthermore, ‘international collaboration is also a key factor for researchers in choosing countries, so the UK’s highly collaborative approach helps us attract global talent’.

A new report by the Innovation and Research Caucus presents a conceptual framework for understanding the reputational impact of investment in international R&I activity. Literature reviewed to develop the framework indicates that ‘the UK’s investment in international R&I can significantly enhance the positive reputation of the UK’. This focuses on the UK’s reputation ‘as a ‘Great Research, Science and Innovation Nation’ with unique R&I capabilities, resources, talent and skills’. The report makes recommendations in support of continuing to build the evidence base. These include incorporating reputational impacts into programme evaluations and project outcome reports, and further refining methodology for assessing reputational impact.

Barriers to international mobility

Introduction

Evidence identifies a range of barriers to international mobility being experienced by individuals and organisations. This section focuses on barriers identified to attracting and retaining international researchers to the UK. These include upfront costs and the complexity of the UK immigration system, the availability of funding, and barriers to living in the UK.

Evidence base

Immigration system and upfront costs

Evidence gathering by research sector organisations has identified that upfront costs in the UK visa system, and the complexity and length of the UK visa process, are key barriers to relocation for researchers.

Previous analysis published by the Royal Society highlights that upfront visa costs (including application fees, fees for dependents, and the Immigration Health Surcharge (IHS)) are barriers to attracting international talent. Between 2019 and 2024, total upfront immigration costs in the UK increased by up to 126%, depending on visa type.

The analysis found that ‘the biggest upfront cost component in the UK is in the IHS which in February 2024 increased by 66%, from £624 to £1,035 per person per year’ of visa applied for.

When including the upfront IHS costs, the GTV is ‘the most expensive visa’ in comparison with similar research visa routes offered by competitor science nations (when comparing both upfront the costs for an applicant as well as total upfront costs, paid by both applicant and employer). For a family of four to come to the UK, including the main GTV holder and three dependents, the upfront costs are £20,974 for a five-year visa.

As the Royal Society acknowledge, making country-to-country comparisons can be difficult due to variations in available visa types and healthcare provision. Further evidence is needed about the exact disincentive these upfront costs pose in attracting and retaining researchers in the UK. (The ‘New evidence for 2025 section’ summarises the latest analysis of visa costs published by the Royal Society which build on the findings presented in this section.)

Insights on the impact of increased upfront costs in a 2024 CRUK report include a projected 44% increase in costs. This is to recruit the same number of posts at cancer research institutes in 2023 to 2024 as in 2022 to 2023. Associated challenges include unfilled roles and delays to research projects, as well as less money directly available for research costs as a result, including for research groups and specialist facilities (see the ‘New Evidence for 2025’ section for further details of these costs).

In the 2024 wave 2 Home Office Global Talent visa evaluation, 27% of visa holders surveyed suggested that ‘clearer information was needed around the Immigration Health Surcharge’. A larger proportion of respondents felt the IHS was unfair than fair (65% and 24%, respectively).

Most analysis has focused on academic researchers, despite a larger, and growing proportion of UK researchers who work in businesses. This includes as people working in research-related roles in business tend to be less well-defined and more difficult to reach.

A 2023 evidence gathering exercise by the Campaign for Science and Engineering found that recruiting international talent is costly and complex, in relation to the resource and expertise needed to navigate the immigration system. This is also noted as impacting smaller businesses who may have fewer administrative or financial resources and who may be less likely to recruit skilled international talent as a result.

Experiences of the UK immigration system for different groups

A UKRI-commissioned study by the EDI Caucus (forthcoming) found that international researchers with protected characteristics and caregivers are likely to experience disproportionate challenges in relation to the UK visa system. This includes the costs and complexities of the system.

The data showed that ‘researchers from racial minorities, those with disabilities, and women were particularly affected, encountering additional hurdles in terms of financial support, access to services, career progression, and institutional biases’. These challenges significantly impact the international mobility and career advancement of these researchers, resulting in a less diverse and inclusive research environment.

Visa costs were identified as potentially having a disproportionate impact on researchers from lower income countries and for researchers who are single parents or have larger families.

The study also found that UK visa rejections lack clarity and often vary, posing potential inconsistencies and perceived bias, with evidence highlighting a notable impact on African and Asian applicants.

A RAND Europe survey in 2018 identified administrative challenges to the UK visa system, with the length of the visa process identified as an issue particularly for early career researchers. A quarter of researchers from Africa and Asia reported difficulties in obtaining a visa that affect relocation. They were also ‘more likely to report visa-related challenges related to visiting other countries than were their colleagues with a European or North American nationality’.

A 2023 report by the Royal Society on short-term mobility arrangements also identified that ‘refusals are skewed towards applicants from the Global South’. It showed lengthy processes due to ‘delays in the Academic Technology Approval Scheme (ATAS), required for researchers of certain nationalities coming to the UK to work in areas deemed sensitive’. For further discussion on ATAS, see the ‘Methodology’ section.

Evidence on the impact of visa costs for those at an early stage of their career includes analysis by CRUK. This highlights that ‘a postdoc at the CRUK Manchester or Scotland institutes would now spend 10% of their total income for a three-year position on immigration costs to bring three family members.’

Visa costs have also been identified in a Universities UK International report as a barrier to the success of international postgraduate research students. This includes those seeking to gain a PhD or masters qualification primarily through research, alongside visa restrictions in working hours.

Barriers to living in the UK

Findings of the first wave of the UK Research and Innovation Workforce Survey in 2022 show that respondents with non-British citizenship viewed the biggest barriers to living in the UK to be the following:

- ‘level of pay and benefits, or maintaining your standard of living’ (30%)

- ‘immigration and visa requirements’ (24%)

- ‘finding adequate accommodation’ (15%)

- ‘availability of suitable opportunities to advance your career’ (14%)

- ‘working hours’ (14%)

- ‘transfer of pension or other benefits’ (12%)

- ‘finding suitable care or education for dependents’ (11%)

- ‘ability of family members to live or work in the UK’ (11%)

- ‘lack of research facilities or infrastructure’ (10%)

- ‘workplace discrimination and harassment’ (10%)

- ‘other financial consideration, including cost of relocation’ (10%)

- ‘UK culture’ (9%)

- ‘maintaining contact with your professional network’ (6%)

- ‘qualification requirements’ (2%)

- ‘language requirements’ (1%)

25% responded that nothing had made it difficult for them to work in the UK (Research and innovation (R&I) workforce survey report, 2022). See sections of the report titled ‘New evidence for 2025’ for findings from the second wave of the survey.

The EDI Caucus (forthcoming) study on barriers to diversity within the R&I sector, focusing on challenges in the immigration system, also identified challenges to accessing services. This included healthcare services and support. The study also identified financial challenges including the impact of childcare costs.

An evidence gathering exercise by the Campaign for Science and Engineering in 2023 highlights that ‘more needs to be done to create a welcoming environment to attract and retain talent’. This includes ‘considerations around the quality of life, such as affordability of housing, schools, infrastructure, and cultural support, amongst others.’

Uncertainty experienced by EU researchers has been identified as a factor influencing some in the UK to return to their home country. The increasing difficulty of recruiting EU and EAA researchers has also been noted in a CRUK report as a challenge following the UK’s exit from the EU.

The impact of an unwelcoming environment, including due to ‘political rhetoric’, has also been reported in a Universities UK International report as a barrier to the success of international postgraduate research students coming to the UK to work and study.

In the 2024 wave 2 Home Office Global Talent visa evaluation visa holders identified challenges to living in the UK linked to housing and the cost of living. However, it also found that the majority of respondents were planning to settle in the UK. One of the reasons given including due to ‘the UK’s tolerance towards foreigners, multi-cultural identity and sense of fairness’.

Respondents’ motivations for initially applying for a GTV included ‘the perception of the UK as being tolerant and friendly towards immigrants’, with ‘tolerance towards LGBT+ rights and acceptance of same sex relationships’ being ‘highlighted as a positive feature of the UK’.

Funding

The MORE studies consistently indicate that research funding is perceived to be one of the biggest barriers to mobility. In 2019, the UK scored just below the EU average for researchers’ individual satisfaction on the availability of research funding, significantly lagging behind Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

MORE4 data also suggests that both PhD students and researchers perceive funding for mobility and finding a suitable position to be significant mobility barriers.

New evidence for 2025

New reports have highlighted the impact of comparatively high upfront visa costs on researcher mobility and research organisations, and the scope to support researchers to navigate the immigration system. Evidence published during 2025 also continues to show pay and benefits as a key challenge of living in the UK identified by the research workforce.

As noted in the section on ‘What makes the UK attractive’, supporting researchers in accessing the immigration system can potentially attract prospective researchers and enable retention of existing staff. New reports also highlight the scope to address concerns that the UK is less welcoming to international talent, including in the context of the UK’s exit from the EU.

Immigration system and upfront costs

New 2025 analysis of upfront visa costs published by the Royal Society compares upfront immigration costs between the UK and 17 competitor nations. Key findings include that ‘total upfront costs remain significantly higher in the UK than other countries’. This includes an increase ‘by up to 3% from 2024 to 2025 depending on visa type’ and ‘by up to 128% in the six years since 2019 (79% in real terms)’.

The largest upfront cost continues to be the IHS and, including the IHS cost, the GTV remains ‘the most expensive visa compared to other leading science nations’.

The analysis also highlights that ‘the UK has the second highest costs for settlement for visa holders among European nations with dedicated researcher visa categories’. This includes that ‘UK settlement costs are now 217% higher than the average across countries including the UK, and 336% higher when the UK is excluded’.

As previously noted, and acknowledged by the Royal Society, making country-to-country comparisons can be difficult, and further evidence is required to understand how such upfront costs can impact on researcher mobility to the UK.

A CRUK report on UK-EU collaboration highlights that ‘the consequences of the UK’s from the EU, higher visa costs, COVID-19 and the cost-of-living crisis have negatively impacted international recruitment and mobility over the past five years’. Visa costs are identified as particularly impacting on early-career researchers and those with lower paid roles, and the UK is now ‘struggling to compete’ to attract talent with other non-EU and EU countries. Reasons include free movement within EU countries and comparatively lower visa and immigration costs in non-EU countries.

A report by researchers at the University of Southampton on UK-EU collaboration in the context of cancer research suggests that, following the UK’s exit from the EU ‘there is a strong sense that EU early career researchers avoid the UK’. They report describes this as ‘leaving a gap in the workforce that is not being filled by domestic or non-EU talent’.

The impact of visa and immigration costs for employers who contribute towards these costs is highlighted in analysis undertaken by CRUK. In the 2024 to 2025, financial year, the total cost of visas for researchers at CRUK institutes was over £870,000.

The report highlights that this is equivalent to ‘funding for two three-year cancer research projects’ or the ‘salaries of 22 postdoctoral researchers’. These upfront costs present a challenge to the recruitment process, with evidence of researchers rejecting roles due to the immigration costs to bring their families to the UK.

Case studies collated by the Campaign for Science and Engineering have identified barriers in the visa system for 15 research and development organisations. Key barriers include ‘high visa costs’ (including the IHS), ‘complex visa policy’, and ambiguity about eligibility for the Global Talent visa.

Upfront costs are noted as impacting on researcher decision-making during the recruitment process, particularly for those that are ‘early career, from low-income countries, and those with dependents’. Costs are highlighted as a deterrent to applications for postdoctoral researchers, technical roles, and senior leaders including ‘for fear that they will struggle to recruit their teams’. Variation in financial support for visa fees that institutions are able to offer is noted as being a ‘high financial burden’ for those that do offer it and creating a ‘comparative disadvantage’ for those that do not.

A recent survey by the Universities and Colleges Employers Association of UK higher education institutes explored the impact of immigration rules changes on the recruitment and retention of international staff. Key barriers to recruitment include:

- ‘vacancies no longer meet salary threshold(s) under the Skilled Worker route’ (73 of 93 organisations responding)

- ‘increased immigration costs for individuals and institutions’ (54 organisations)

- ‘visa or immigration costs, or both, for institution and visa processing times’ (37 organisations)

The most frequently reported reasons for difficulty in retaining international staff were ‘high immigration costs’ and ‘visa renewal issues’.

The majority of organisations reported providing financial assistance for employee immigration costs, with some organisations noting concerns regarding the affordability and sustainability of doing so.

A report by the House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee presents evidence on the impact of visa policy, including upfront costs, as a barrier to attracting research talent to the UK. The report highlights that ‘visas for scientists remains a critical area where policy must change’ with ‘the need for a proactive policy to attract global scientific and technological talent’. This includes ‘by addressing the high upfront costs’ and current policy on the IHS as an upfront cost which currently cannot be repaid over time.

Barriers to living in the UK

The second wave of the UK Research and Innovation Workforce Survey undertaken in 2024 asked non-British respondents about barriers to living in the UK.

In 2024, the four biggest barriers to living in the UK reported by respondents with non-British citizenship were:

- ‘level of pay and benefits, or maintaining your standard of living’ (41%)

- ‘suitable opportunities to advance their career’ (18%)

- ‘finding adequate accommodation’ (17%)

- ‘immigration and visa requirements’ (17%)

These four barriers also constituted the main four barriers identified in the first wave of the survey in 2022. ‘Level of pay and benefits, or maintaining your standard of living’ was the most frequently reported barrier to living in the UK in both the 2022 and 2024 surveys.

As noted in the section on ‘What makes the UK attractive’, new evidence has also identified that perceptions of the UK being a less welcoming place are impacting on the attractiveness of the UK to researchers.

The cited report by researchers at the University of Southampton includes a recommendation to address ‘perceptions that the UK is not welcoming to international workers’.

Findings of a nationally representative survey of UK adults and focus groups undertaken and published by the Campaign for Science and Engineering found however that ‘international students and researchers are seen as beneficial to the UK’.

This includes as ‘international researchers can diversify ideas and culture, improve the UK economy, increase collaboration and strengthen the quality of UK R&D’. In addition, a majority (52%) would prefer universities in the UK to recruit the best global talent even if it means more immigration to the UK.’

In 2025, the Campaign for Science and Engineering published a Guide for Engaging the Public with Researcher Immigration to support in communicating the value and contributions of international researcher immigration to the UK. This includes a series of principles for public messaging on research migration, based on testing messaging to generate insights via qualitative and quantitative research.

Limitations of the evidence base

While the evidence used in this report sketches a picture of the international mobility of researchers, the studies included in this summary have some limitations. This section considers these limitations and highlights gaps in the available evidence base.

Due to the variation in defining international mobility, it is difficult to draw general conclusions about the prevalence of international mobility, and it should be noted that the strength of some studies in this area is limited.

Within this report we have primarily focused more on long-term mobility. To help understand the picture for short-term mobility arrangements, the Royal Society published an analysis of short-term visa costs and processes in the UK and other leading science nations.

What makes the UK attractive

While there is evidence to suggest that progression and job opportunities are an important motivation for moving to the UK, the sample sizes of these studies were small and geographically limited.

Further evidence is needed on the impact of research funding schemes in enabling international mobility, including specifically in attracting international researchers to the UK (see the section on ‘Research funding schemes’).

There is little comparative evidence of how different countries support and promote international mobility, and there are challenges to making like-for-like assessments to compare between countries.

Demographics and mobility of the research workforce

This review did not find many studies that looked at the international mobility of research team members and specialists. For example, technical or methodological experts, language specialists, professionals in engineering, data science and so on. There is scope for future analysis to look at how international mobility varies by researcher occupation and sector and discipline (see the ‘Demographics and global mobility’ section)

Recent analysis published by the OECD on international talent flows between countries is supportive ‘of a “circulation” paradigm’. However, the OECD highlight that ‘circulation can mask qualitative differences between those leaving and those arriving, such as variations in skills, experience, or research fields’.

Gaps in current evidence on talent circulation which the OECD are seeking to address include ‘longitudinal data analysis strategies to track movements within and between sectors such as academia, industry, and government’. As well as ‘key channels for knowledge exchange and collaboration’.

This will generate insights on ‘career pathways, the skills required for different roles, and the factors that influence researchers’ decisions to move across sectors and occupations’.

Impact of international mobility and collaboration

While the evidence base points to the reported benefits of international mobility and collaboration, it is difficult to quantitatively measure the impact of international mobility on research performance.

The impact of international mobility is difficult to measure, and the most widely used measurement, Field Weighted Citation Impact (FWCI), is narrowly defined and not inclusive of the wide range of research outputs and impacts. As a signatory to the 2013 San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment, we are mindful of how inappropriate metrics can give rise to perverse incentives.

Evidence published by the OECD indicates that international collaboration is positively correlated to the citation impact of research publications. This includes publications by incoming researchers to the UK having a 13% higher FWCI than those of UK-based researchers who are not mobile.

However, the FWCI of researchers who return to the UK and of researchers who leave the UK for another country does not differ significantly from those who stay in the UK.

A focus within existing evidence on publication data does not present a full picture of the potential impact of and benefits from research arising from international mobility and collaboration. This includes the potential broader contributions of such research to the economy and to society, and in addressing global challenges.

Barriers to international mobility

It is difficult to quantify the impact that upfront visa fees, including the IHS, have on attracting and retaining international talent, as to do so, we would require knowledge of individuals who have turned down an offer to come to the UK.

As noted in the main ‘Barriers to international mobility’ section, making country-to-country comparisons can be difficult. This includes when seeking to compare different countries’ immigration fees, as these systems are complex and varied. This also includes as some countries require separate health insurance, in contrast to the UK requiring upfront payment of the IHS for immediate access to the NHS.

Further evidence is needed about the exact disincentive that upfront costs, such as the IHS, pose in attracting and retaining researchers in the UK.

Areas for future research

While this report sets out many of the key dimensions in global mobility, there are areas where there is limited information. Future evidence-gathering exercises should aim to help reduce these gaps in evidence.

By growing the evidence base in these areas, there is scope to develop a more granular understanding of researcher mobility to the UK in order to inform future policymaking. A robust evidence base is central to developing policies and programmes which can address identified barriers to mobility experienced by international researchers.

Effect of immigration rules

The Immigration White Paper published in May 2025 proposes making visa routes for highly skilled international talent simpler and easier to access as part of delivering the UK government’s mission to promote growth. It is important that existing evidence on barriers to mobility is used to inform these developments, and that further evidence is gathered as part of implementing any changes to understand the resulting impact. There is the potential to explore the impact of changes to the visa and immigration system on the mobility of researchers supporting Industrial Strategy priority areas.

Within this context, there is scope to explore in more detail how researchers use UK visa routes over time. This includes understanding the visa routes utilised by researchers coming to the UK for shorter periods of time.

More recent evidence is needed on the effect of the Home Office immigration rules on international researchers’ attitudes to, and experiences of, mobility. This includes changes to the Skilled Worker general salary threshold and following potential changes to the eligibility criteria for settlement. This also includes the implementation of the latest changes to UK visa fees and upfront costs for international researchers and their dependents.

There is a growing body of evidence on the impact of upfront visa and immigration costs for researchers, research funders and employers. There is further potential to identify the overall opportunity cost to the research and innovation sector. UKRI continues to prioritise gathering evidence on the impact of the upfront costs (particularly the IHS) on attracting and retaining international talent.

An OECD report published in 2015 found that visa restrictions can have statistically negative effects on both scientist flows and collaborations, decreasing them by as much as 50%.

Research funding

There is limited evidence on the impact that research funding schemes have on fostering international mobility.

The section on ‘Investments and interventions in the research sector’ outlines a range of new funding schemes to support international researcher mobility, including the Global Talent Fund and the Choose Europe programme. Evaluations of such schemes can contribute to addressing the limited available evidence on the impact of research funding schemes on researcher mobility.

During 2026, UKRI will be undertaking evaluation activities to understand the impact of the Global Talent Fund, as well as seeking to collate available evidence on the evaluations of similar schemes. The Global Talent Fund enables 12 UK research organisations to rapidly recruit and embed teams of international researchers supporting Industrial Strategy priority areas. The fund covers both relocation and research costs, recognising that evidence indicates relocation costs as a potential barrier to mobility.

Demographics and global mobility

Little is known about the demographics of globally mobile researchers, including both the short-term workforce as well as researchers relocating to the UK. Further analysis is needed on how global mobility varies by researcher occupation and sector or discipline.

Evidence is needed on the effectiveness of EDI policies in relation to international researcher mobility.

Research commissioned by UKRI and undertaken by the EDI Caucus (forthcoming) identified a range of challenges, including financial and administrative barriers, experienced by researchers with protected characteristics in navigating the immigration system.

The study highlighted further practical and financial challenges that researchers with protected characteristics can experience once in the UK, including accessing services and support, as well as to progressing their careers.

Additional research on the effectiveness of particular policies and practices seeking to address financial and administrative barriers to engaging with the immigration system would support in guiding policy in this area. Further research is also needed to identify effective policies and practices to provide support to international researchers establishing themselves in the UK.

Global mobility patterns

Future analysis could examine the impact of researchers’ mobility patterns on the success of international collaborations, career progression across career stages and disciplines. As well as the extent to which different periods of short-term mobility (for example, conferences or placements) are equal to long-term mobility in terms of impact on career progression or recruitment opportunities.

Within the current climate, there is scope to identify whether developments in the international research landscape are translating into changing patterns of global mobility.

Societal impact of global mobility

There is a lack of evidence around the social implications of global mobility, both on a personal level for researchers and in terms of research outcomes.

For individual researchers, this includes the considerations involved in being internationally mobile, the intended benefits of becoming mobile, and the impact of coming to a new environment.

At a societal level, this includes a lack of evidence on the benefits that research brings for UK citizens. Most studies focus on benefits to the economy, or to researchers’ careers or their academic output and forming of new networks.

As a literature review commissioned by the Royal Society highlights, ‘the advantages of mobility have been chiefly assessed in terms of publication, which does not present a full account of the benefits to society that research provides’. In addition to publications, researchers may contribute to a range of research outputs, for example new inventions, software, protocols or policies.

There is scope for future evidence-gathering on the impact of initiatives to support international mobility to explore a wider range of personal and professional outcomes, as well as broader societal benefits.

Next steps

This report aims to increase understanding of the global mobility of researchers, including the barriers and motivations to do so, to highlight the impacts of mobility and identify where the gaps in knowledge are. This centralised summary of evidence on global mobility will act as a shared point of reference in the sector, to help provide the basis for evidence-based policy proposals and stances.

UKRI publish an annual update to this evidence report with the aim of providing a succinct snapshot of the current evidence on international mobility, along with a summary of the evidence that assesses how attractive the UK is to international researchers. We encourage you to contact the team if you have any suggestions for evidence to include, or if you have any other feedback. To share any suggestions or feedback on this report email globalmobility@ukri.org

Methodology

The evidence report is based on literature reviews and data between 2010 and 2025. These sources were identified through online searches, engaging with various organisations for guidance and utilising existing UKRI data providers, such as the HESA.

It aims to summarise the latest evidence on international researcher mobility to the UK from the identified sources and will be updated as new information and data becomes available. A variety of sources have been used from reputable sources which are listed. Any analysis done internally has been quality assured. Evidence prior to this time period or that can no longer be accessed has been removed to ensure that the evidence accurately reflects the landscape. An exception to this rule is if the point made by the evidence source is not specific to that time period.

New evidence published during 2025 is presented under specified headings for ease of identification by the reader. Summaries of evidence published prior to 2025 are provided in preceding sections for context. A fuller overview of evidence published prior to 2025 can be found in the Global Mobility evidence report 2024 update.

Definitions

The Immigration Health Surcharge: the surcharge is an upfront cost paid as a part of the visa application, and grants the visa holder access to free health services in the UK. The surcharge is calculated based on the length of visa being applied for.

Definitions based on the International Comparative Performance of the UK Research Base report

See the International Comparative Performance of the UK Research Base report

Migratory mobility pattern: researchers who stay abroad or in the UK for two years or more.

Transitory mobility pattern or temporary mobility pattern: researchers who stay abroad or in the UK for less than two years.

Definitions based on OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms

See the OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms

Researchers: professionals engaged in the conception or creation of new knowledge, products processes, methods, and systems, and in the management of the projects concerned.

Research personnel: all persons employed directly on research and development (activities), as well as those providing direct services such as research and development managers, administrators, and clerical staff.

Technicians: persons whose main tasks require technical knowledge and experience in one or more fields of engineering, physical and life sciences, or social sciences and humanities. They participate in research and development by performing scientific and technical tasks involving the application of concepts and operational methods, normally under the supervision of researchers. Equivalent staff perform the corresponding R&D tasks under the supervision of researchers in the social sciences and humanities.

Definition derived from What is Field-weighted Citation Impact from Scopus

See What is Field-weighted Citation Impact from Scopus

Field-weighted citation impact: the ratio of the total citations actually received by the denominator’s output, and the total citations that would be expected based on the average of the subject field.

UKRI’s approach to Global mobility

The UK immigration system offers a range of targeted routes for those who lead, undertake and support research and innovation. The UK immigration offer includes provision for mobility, inward and outward, for both long-term migration with routes to indefinite leave to remain and short visits for knowledge exchange, conferences, training, and research collaboration.

It is important that UKRI enables a diversity of individuals to easily transition not only between roles, but also between institutions, academia and industry, and across national boundaries.

The UKRI Global Mobility team, as part of the Research and Innovation Culture and Environment team, works to create the conditions to improve the culture and environment of the UK research and innovation system. We do this by synthesising and analysing evidence and effective practices from across the R&I system. This is to derive insight and to develop interventions, which are then delivered across our organisation to improve the UK’s R&I culture and environment.

We aim to improve the international and cross-sectoral mobility of researchers and their teams by developing existing schemes, including the Global Talent and short-term visa schemes, and through identifying new opportunities to:

- support career progression

- broaden access to skills

- build national and international networks

This includes widening eligibility for the Government Authorised Exchange (GAE) Future Technology Research and Innovation (FTRI) scheme operated by UKRI to further enable temporary collaborations for businesses undertaking research in critical technology areas.

We work towards addressing key barriers to the international mobility of researchers and their teams to ensure the immigration system acts as facilitator to mobility. We are particularly aware of high comparative and upfront costs of UK visa fees and continue to work with the government to improve our approach to attracting global talent to the UK.