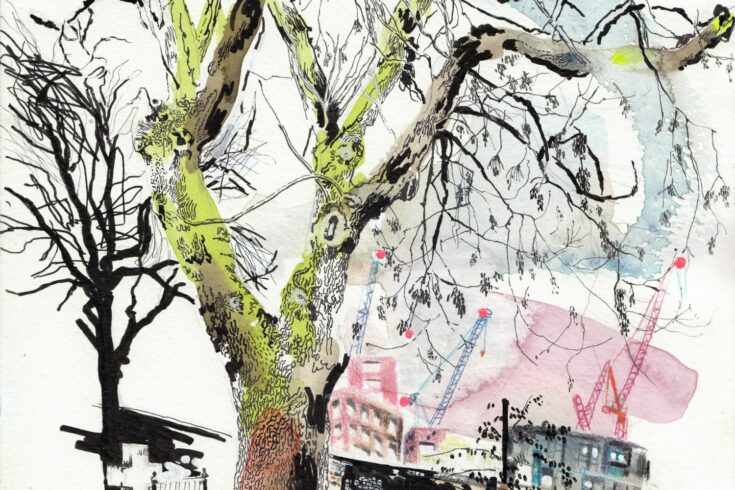

Imagine a world without trees: no boughs to provide shade, no autumn leaves with their bursts of colours, no way to break up the concrete of cityscapes. The world would certainly look less attractive.

But trees do so much more than decorate our villages, towns and cities. Healthy trees bring sensory pleasure, nutritious food and they even clean up after us.

Oak trees: butterflies and birdsong

The oak tree is the national tree of England and one of the most beloved trees in the world. They are an ecological epicentre, supporting a large diversity of species.

The Protect Our Oaks Ecosystems project, part of the Tree Health and Plant Biosecurity Initiative (co-funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), together with the Forestry Commission, DEFRA and the Scottish Government) mapped the species supported by oaks in the UK.

If you’ve ever delighted in seeing a colourful butterfly flitting around, then you may have an oak tree to thank for the sight. Of the 235 species of moth and butterfly that use oak, 67 use oak exclusively.

The birdsong that puts you in a positive frame of mind for the day could also be thanks to an oak tree – 38 species of bird use oaks for roosting, feeding and breeding.

As the Protect Oak Ecosystems project team noted, humans have formed lasting attachments to oak trees and the species they support. Supporting the health of oak trees means protecting the pleasure we get from hearing birds and seeing butterflies.

Bigger, better apples

If you imagine a tree covered in bugs you might think it’s a sign of bad health, but in the case of certain apple trees it leads to great things. Namely, bigger, better fruit.

A 2014 NERC-funded study found that apples from trees pollinated by insects were bigger, rounder and more desirable.

The study was carried out on six Cox and Gala orchards in the apple-growing region of Kent, and it also showed that these two apple varieties are worth just under £37million to the economy.

While humans rely on trees for apples, those trees rely on pollinating insects like bees and hoverflies. Dr Mike Garrett from the University of Reading, who led the project, explained:

To maximise the quantity and quality of apples, we’d need to increase both the abundance and diversity of pollinating insects.

That way, when you get a particularly bad season for one pollinator species, there would be a healthy stock of other insects to come in and do the work.

Clean air and climate change

Trees perform a very helpful service for humans: they tidy up after us, in the atmospheric sense, by absorbing up to one third of anthropogenic carbon.

Will they be able to do this forever? And, without meaning to impose, could they do it better?

The Birmingham Institute of Forest Research (BIFoR), part of the University of Birmingham, has created a living laboratory to find out.

A mature oak woodland in Staffordshire is now home to an outdoor experiment, known as the FACE ecosystem. The canopy trees are at least 160 years old, and the site has been forested for the last 400 years.

Ove a 10 year period scientists are exposing swathes of the woodland to the carbon dioxide concentrations that the planet is likely to experience by 2050. And we’ll be able to find out what direct and indirect impact this will have on humans.

It is part of a global collaboration, working with a similar site in Australia and one in the Brazilian Amazon.

NERC has funded the QUINTUS project at the BIFoRFACE facility, which is carrying out detailed measurements of nutrient cycling, and help find out how a mature, temperate forest responds to rising atmospheric carbon dioxide.

In Professor Rob MacKenzie’s words: “This is big science”. The BIFoR FACE facility provides a real world experiment to improve climate projections and evaluate risks to forest ecosystems and the services they provide.

Protection

Trees can also be protectors. Mangroves, which are trees that grow along coastlines, provide many ecosystem services.

Professor Mark Huxham from Edinburgh Napier University has studied mangroves in East Africa for20 years and even helped set up Mikoko Pamoja in Kenya, the world’s first project to fund conservation through the sale of carbon credits.

He points out that healthy mangroves provide huge benefits to the people who live beside or near them.

Mangroves act like a buffer against waves, storms and tsunamis. They’re a natural coastal wall that would cost millions to replace.

Their intricate roots and shoots give protection to young fish and shellfish, many of which are depended on by local communities for food.

Mangroves provide benefits for all of us, not just their immediate neighbours. They capture many times more carbon than territorial forests thanks to their waterlogged sediments and so help in the fight against a warming planet.

Last updated: 8 May 2025