Max Müller (1823-1900) was one of the founders of the study of comparative religion, and a key figure in the development of the study of Sanskrit literature and the Indo-European language family. As a classicist, he is a near unavoidable and compelling figure, and he once wrote:

If I were to look over the whole world to find out the country most richly endowed with all the wealth, power, and beauty that nature can bestow—in some parts a very paradise on earth—I should point to India. If I were asked under what sky the human mind has most fully developed some of its choicest gifts, has most deeply pondered on the greatest problems of life, and has found solutions of some of them which well deserve the attention even of those who have studied Plato and Kant— I should point to India. And if I were to ask myself from what literature we, here in Europe…may draw that corrective which is most wanted in order to make our inner life more perfect, more comprehensive, more universal, in fact more truly human, a life, not for this life only, but a transfigured and eternal life—again I should point to India.

An unmissable opportunity

I have worried about our legacy from the Indus for years, and observed the vital contemporary relationship between India, the UK and the world. But until last year I had never visited, and the 15th anniversary of UK Research and Innovation’s (UKRI) India Office in New Delhi, and the celebration of our most recent projects, was an unmissable opportunity.

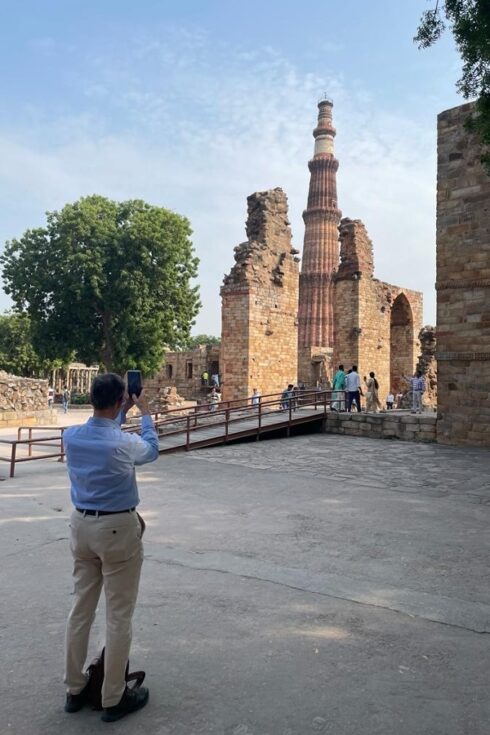

Seeing India at first hand was a privilege. The Qutb Minar complex was a fascinating array of landscape and architecture, an example of the importance of cultural heritage, just one of the many areas where UK and Indian expertise intersect.

Our UKRI office is located in the British High Commission, part of a more modern architectural synthesis of styles, the Lutyens designed landscape of New Delhi. It can often take time to nurture partnerships, but at a wonderful reception in the grounds of the British High Commission, with many Indian stakeholders and UK universities represented, I was able to reflect on how we have built our partnerships.

Professor Christopher Smith visiting the Qutb Minar. Credit: Jennie Lambert

Key role in partnerships and collaborations

For the last 15 years, UKRI India has played a key role in making partnership feel easy and creating collaborations that matter. We have done this by facilitating co-funding for over 250 research and innovation projects; through our close links with our partners across the Government of India and His Majesty’s government in the UK; and through our deep and far-reaching network that spans academia and business across both countries.

The UK-India partnership is now worth close to £400 million or Rs 4,100 crore, with partnerships with 16 government and other agencies which has supported over 200 research institutions and 100 industry partners. In partnership with the Government of India, we have invested:

- £65 million in health and wellbeing

- £28 million in innovation and adoption

- £120 million in climate, energy and environment

- £13 million in technology and skills

- £11 million in culture and societies

Announcing globally significant initiatives

And at the anniversary we were able to announce globally significant initiatives such as four new projects co-funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council in the UK and Department for Atomic Energy in India.

The research aims to develop skills, technologies and knowledge in areas such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, bio-imaging and accelerator development that can be applied to improve and augment scientific research carried out at large scientific infrastructures in the UK and India and have a tangible impact in areas such as cancer treatment. UK participation in this programme is worth £5.3 million.

UKRI India 15th anniversary event. Credit: Victoria McGuire

Heading south, we saw a different India in Bangalore. If the science partnerships represent the best of our most advanced technological capacity, the India Foundation of the Arts is a brilliant demonstration of how arts and culture are equally essential to our individual and community lives, and for a more equitable and just world. Their wonderful projects from schools to community theatres, telling the many stories of this extraordinary continent, were an inspiration.

The power of collective effort

We know we must integrate our thinking. The most complex problems are best solved when different disciplines work together. We must trust the power of this collective effort and not permit ourselves to be constrained by artificial structures.

We must aim for global good. UK-India research and innovation has already demonstrated the potential to deliver impact that improves lives globally. Cradle Vital Signs Alert is developed by the Medical Research Council and Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office in the UK and Department of Biotechnology in India. It is the world’s first medical device to detect shock and high blood pressure in pregnant women. It could cut maternal deaths in developing countries by up to 25%, saving more than 70,000 lives a year. This collaborative spirit is crucial in addressing challenges which go beyond our borders.

Next-generation leadership

We must invest in next-generation leadership. It is our responsibility to give future academics and innovators the skills and the means they need to make global partnership more natural and more sustainable.

We should be more curious. Powerful partnerships come from the most surprising places. That is why we must embrace new methods, explore new opportunities and be open to new ways of collaborating.

Challenge and promise of our time

In the Bangalore Science Gallery, the brilliant director Jahnavi Phalkey and her terrific team were gearing up for the exhibition Carbon, which starts this year. As the museum puts it:

Carbon is an archive of buried sunshine, carrying memories of life on earth. It jumbles the divide between substance and phenomena; caught between finitude of nature’s resources and the near infinite wonderous potential it holds. It is urgent that we better understand both carbon energy history and the futures it enables.

Art and science, history and imagination, the deep past and our fragile future – this is the challenge and promise of the science of our time.

EM Forster, who wrote a famous novel on India, also wrote the famous injunction, Only connect!

For me this was a visit about connections, the ones we have built but just as importantly those we need to develop. I can’t wait to go back and learn more, and I look forward enormously to the next 15 years of this extraordinary partnership.